The fifth volume of “Studia et Documenta” (2011) has been published

The premiere of the latest film by Roland Joffé, There Be Dragons is attracting an ever increasing interest in the life and history of Josemaría Escrivá de Balaguer, the founder of Opus Dei. One of the characters that appears with Escrivá in this film is “Juan” (Juan Jiménez Vargas), a young an energetic doctor who accompanied him in times that were very difficult, while escaping the religious persecution during the Spanish civil war.

The premiere of the latest film by Roland Joffé, There Be Dragons is attracting an ever increasing interest in the life and history of Josemaría Escrivá de Balaguer, the founder of Opus Dei. One of the characters that appears with Escrivá in this film is “Juan” (Juan Jiménez Vargas), a young an energetic doctor who accompanied him in times that were very difficult, while escaping the religious persecution during the Spanish civil war.

The number 5 issue of the journal Studia et Documenta (2011), which has just been published, includes a biographical note about “Juan”; this note was written by Francisco Ponz and Onésimo Díaz. The first part of the article takes us straight into the atmosphere of Joffé’s film, with the fantastic adventures of Jiménez Vargas in his efforts to save both his own life and that of the Founder, from hiding place to hiding place in Madrid and, afterwards, across the Pyrenees. But, after the War, we see him embarking on a prestigious medical career in the Spanish university. Later, he undertook the really demanding adventure of the start up, with limited human and economic resources, of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Navarre. This was a colossal undertaking, an undertaking which needed all the human and supernatural bravery and determination of Vargas.

The journal dedicates other interesting articles to the history of Opus Dei and its Founder. The traditional monographic section refers to various initiatives in the educational field inspired by St. Josemaría and carried out, with his encouragement, by Opus Dei members in different countries. This is the continuation of a series of studies published in previous issues of Studia et Documenta. The section in question is titled: “The university, work and business between decolonization and development. Initiatives promoted by Saint Josemaría during the 1950’s and 1960’s”. The article looks at four apostolic undertakings: a hospitality and services school (Kibondeni), in Kenya; a business school with global prestige (IESE), in Spain; and two university residences (Müngersdorf and Netherhall House) in Germany and the United Kingdom, respectively.

The sociological contrast between the Kenyan women, with minimum economic resources, who attend the Kibondeni classrooms and the high power executives who take part in the training programs in the IESE, could not be greater. “However –as Fernando Crovetto writes in the introduction–, in both cases the goal is to give formation imbued with a Christian spirit which is at once pioneering, up to date and of high quality”.

Each of these initiatives had to overcome important challenges. When the IESE commenced, for example, training programs for managers were virtually unknown outside the United States and France, and –as Antonio Argandoña relates in his article– the IESE had to carry out its own mission, a mission which had been entrusted to them by the founder of Opus Dei: it was a question of helping the people responsible for the promotion, management and development of financial corporations to be exemplary Christians and to act at all times in harmony with their faith. At the same time it was necessary to give them a professional formation of the highest quality so as to be able to exercise a profession which would have an ample social impact.

The creation of a school for the training of women such as Kibondeni in the Kenya of the 1960’s, was possibly an even more innovative enterprise. As Christine Gichure shows, the educational project was aimed at persons of every race, tribe and religion at a time when racial segregation was still in force. The colonial lifestyle, on the other hand, presented apparently insurmountable prejudices against the education of women and their adequate social advancement.

The university residence, Netherhall House, in London, came about with the intention of offering accommodation to university students of all races, nationalities and religion against the backdrop of decolonization, as James Pereiro explains in his article. In turn, the Müngersdorf residence in Cologne faced a different challenge due to the shortage of economic and human resources available to the promoters, and the difficulties that accompanied its beginnings which have been documented by Barbara Schellenberger.

The Studi e Note (Studies) section, which contains miscellaneous material, has an article by Carlo Pioppi on the interviews of the founder of Opus Dei with church dignitaries during the years of the second Vatican Council. The biographies of Msgr. Escrivá usually relate that between 1962 and 1965, he spoke with many of the Council Fathers; the very detailed work by Pioppi provides valuable information in this regard.

As well as a biographical outline of Juan Jiménez Vargas, this same section contains a biographical sketch of another of the oldest members of Opus Dei: Dora del Hoyo. Salvadora (Dora) del Hoyo (1914-2004) was the first assistant numerary. The article, written by Ana Sastre –who has also written a biography of the Founder–, describes Dora’s early life in Leon and her transfer to Madrid, in 1940, where she worked in the domestic service of a number of houses. While in Madrid, she met Josemaría Escrivá de Balaguer and the first women of Opus Dei. Later on, in 1946, she asked to be admitted into the Work and the very same year, she moved to Rome where she lived and worked until her death in 2004.

As well as a biographical outline of Juan Jiménez Vargas, this same section contains a biographical sketch of another of the oldest members of Opus Dei: Dora del Hoyo. Salvadora (Dora) del Hoyo (1914-2004) was the first assistant numerary. The article, written by Ana Sastre –who has also written a biography of the Founder–, describes Dora’s early life in Leon and her transfer to Madrid, in 1940, where she worked in the domestic service of a number of houses. While in Madrid, she met Josemaría Escrivá de Balaguer and the first women of Opus Dei. Later on, in 1946, she asked to be admitted into the Work and the very same year, she moved to Rome where she lived and worked until her death in 2004.

The Studies section of this issue of the journal finishes up with an article written by Fernando Crovetto. This article is dedicated to the ecclesiastical context of the archdiocese of Saragossa during the first decades of the twentieth century, at exactly the same period as when Josemaría Escrivá lived in this ecclesiastical province and trained as a priest.

The Documenti (Documents) section presents, in the first place, the notes of the historian José Orlandis –recently deceased– on the audiences granted by Pius XII and Msgr. Montini to members of Opus Dei in Roma between 1943 and 1945, some letters by Montini and Orlandis are also included. These documents–introduced and edited by Josep-Ignasi Saranyana– allow us to learn about the early impressions and first hand information that the Pope and the Substitute of the Secretary of State received about Opus Dei.

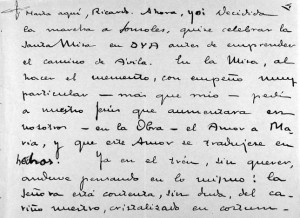

Another document published in this section is an account of a Marian pilgrimage made by Saint Josemaría, with two members of Opus Dei, to the Shrine of Our Lady of Sonsoles, in Ávila in May 1935. This document provides interesting information for the reconstruction of the interior journey of St. Josemaría and the spiritual life –profoundly Marian–, of the Opus Dei members. The presentation and comments are provided by Alfredo Méndiz.

Another document published in this section is an account of a Marian pilgrimage made by Saint Josemaría, with two members of Opus Dei, to the Shrine of Our Lady of Sonsoles, in Ávila in May 1935. This document provides interesting information for the reconstruction of the interior journey of St. Josemaría and the spiritual life –profoundly Marian–, of the Opus Dei members. The presentation and comments are provided by Alfredo Méndiz.

The last document edited in this section is quite short but will be of great interest to Canon Law experts: it consists of a letter from Sebastian Cardinal Baggio to Msgr. Álvaro del Portillo, on the 17th of January, 1983, on the subject of Personal Prelatures. In this letter, the then Prefect of the Congregation for Bishops, informs the Prelate of Opus Dei of an audience with the Pope in which John Paul II had clarified the meaning and scope of the insertion of the canons dealing with personal prelatures in new Code of Canon Law of 1983.

The Notiziario (Academic Events) section is dedicated, this time, to two contributions about The Way: one, by Alfredo Méndiz, as a literary work and the other, by Carmen Sánchez Lanza, from a linguistic perspective.

Just as in previous numbers, this issue also presents a bibliographical section with reviews and critiques and a new installment of the already monumental bibliographical catalogue dedicated to the “General Bibliography” about St. Josemaría and Opus Dei. The first three issues of Studia et Documenta have attempted to provide an exhaustive bibliography about St. Josemaría until 2002, while the fourth issue and the current number deal with the “General Bibliography about Opus Dei”, which will be continued in future issues.